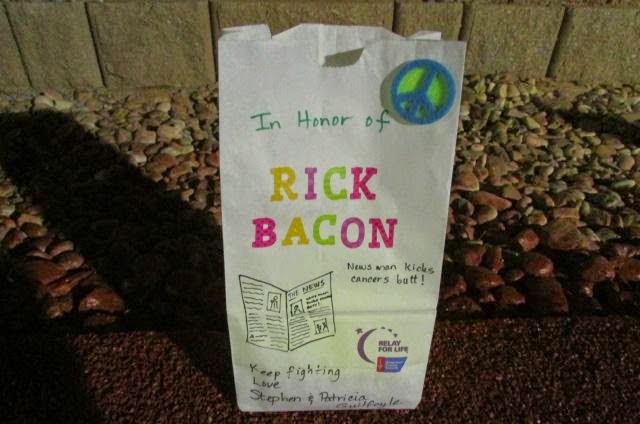

By Patricia Larson Guilfoyle

|

| Rick Bacon was there before Patricia Larson got dressed to marry me, and he was there for me and her long before we ever met. |

CNI's Senior Editor Phil Hudgins just smiled when he had told me Rick wanted to

interview me down in Barnwell. Phil knew me from when I worked in St. Mary's,

Ga., for then-Publisher Dalton Sirmans. Dalton hired this naive 16-year-old who

walked in one day off the street asking for a job. ("Can you write?"

he said. "Sure," I said, and brought him my latest term paper about

graviton particles and the space-time continuum. He hired me the next day, and

one of my first assignments was covering a pipe-bomb explosion at the new

Subway in town. I was hooked!)

Well, Phil knew Dalton, and Phil knew Rick, and Rick knew

Dalton. So before I knew it, I was driving east, trying to figure out where the

heck in South Carolina Barnwell was.

I checked into the one motel in town and went to my room.

Before I had even swung the door open all the way, the phone on the table

started ringing. The sudden noise made me jump -- who in the world knew where I

was? I mean, I wasn't even inside the room yet.

Of course, it was Rick.

"Hi! It's Rick Bacon. Do you want to get something to

eat?"

That was the first thing I realized about Rick: Nothing –

and no one – got past Rick. He was crazy like a fox.

We headed over to Anthony's, one of his regular spots. Of

course, he knew the waitress and pretended to give her a hard time. He ordered

a beer and asked if I wanted one, too. I thought, "I'd never been on a job

interview like this before." But Phil had told me that he was good buddies

with Dalton, so he couldn't be all that weird.

Boy, was I wrong. Rick was a lot weirder than Dalton. Dalton

liked to drive gold-colored cars and made fun of his alma mater, Abraham

Baldwin Agricultural College ("I'm just a poor ol' country boy from

ABAAAAAC," he'd say in his best south Georgia drawl). But Rick had a

thousand crazy voices, which he'd pull out at just the right – or wrong –

moment, and his collection of pig paraphernalia bordered on the fanatical.

Don't even get me started on his cars.

I don't even remember what all we talked about, sitting

there in Anthony's eating open-faced steak sandwiches and drinking beer. I just

remember thinking, "I gotta come work for this guy."

Turns out, Rick had already decided to hire me after talking

with Phil and Dalton, so the entire "interview" was just to test me.

That was the next thing I realized about Rick: Rick was

awesomely cool. He could be exasperating, but only in the nicest possible way,

and for all the right reasons. And he knew what was important as a leader and

manager, whether people liked him or not.

The next three years were a blur, but a couple of moments

will always stand out.

Less than a week into my job, Rick tells me I have to fire a

sports correspondent. The guy had been writing for The People-Sentinel only about

50 years or so, he said. But people at the rec league baseball games he'd been

covering smelled alcohol on his breath a lot. He had to go.

"I've never

fired anyone in my life," I told Rick. "Can't you do it?"

"Nope," he said. "You're the editor. Oh, I've already called

him, and he'll be here in a few minutes. Take him into the conference

room."

Well, the guy came in, still smelling of alcohol. He cried

like a baby when I gave him the news. At 23, I'd never seen a grown man cry in

real life before. After he left and I went back to my desk, which I had

strategically positioned right next to Rick's, I was shaking. I felt awful.

Rick looked over, with that fake-innocent look of his, and

mouthed the words, "You bitch."

That was Rick. Rick could make you laugh no matter what.

Another moment that stands out was back at my desk, sitting

right next to Rick. That week's edition had two big stories in it: One about

students having sex in the bathrooms at Allendale High School, the other about

workers accidentally wringing the necks of two ostriches that were the sideshow

attraction at the local flea market, which happened to be owned by the mayor.

I'm on the phone getting blessed out by the principal at Allendale High, when

the mayor's wife walks in and sits down in the chair beside my desk. She

doesn't care that I'm on the phone, she's just read the paper and is crying/mad

because I've just ruined her husband's reputation.

"They didn't mean to hurt those ostriches – it was an

accident."

Then on the phone: "You think writing about our

problems is what you should be doing? You should be building up our schools,

not tearing them down."

"The birds just got excited and pulled back on the

ropes while they were being unloaded. They wrung their own necks, see?"

"Don't you know these kids are going to read that on

the front page and think they can go have sex in any bathroom now? You're

making our jobs harder."

I hung up on the principal and tried to explain things to

the mayor's wife, but I could not get a word in edgewise.

Then Rick moseys over, puts on his best genteel Southern

persona and takes the woman's hands in his, pulling her gently up from the

chair as he pats her hands. He puts one arm around her shoulder to comfort her,

as he steers her smoothly to the door. He's thanking her, he's soothing her,

he's smiling at her in the kindest way possible. By the time she reaches the

front door, she's smiling up at him and thanking us for the good job we're

doing at the paper.

After the door swung shut, he turned around, bowing with an

exaggerated flourish as everyone in the room applauded. He was the master!

That was the next lesson I learned from Rick: No matter what

problems you're dealing with, other people have problems, too. Sometimes all

people need is a sympathetic ear and a smile to cheer them up. And the Big Guy

could cheer anyone up. Even people who got mad at him still liked and respected

him.

At some point along the way I started calling him Big Guy,

from "WKRP." And since he had a nickname for nearly everyone, he started

calling me PL or PT. Through the few months I worked in Barnwell to when I

moved to Winnsboro, he was always there with support and encouragement, and

when I screwed up or was unprepared, he was there to admonish as well.

I certainly wasn't looking to leave CNI, but when I got an

unexpected job offer to go work up in Fort Mill for literally twice the money,

I dreaded making the call to Rick.

I stumbled my way through the call, explaining that I didn't

want to leave but didn't think I could pass this chance by.

He asked how much

they were offering, and when I told him, he said, "Hell, PT, don't let the

door hit your ass on the way out. You'd be crazy not to take it." He

always gave you his honest opinion.

Over the years I've often found myself asking in different

situations, "What would Rick do?" His advice, his jokes, his voice,

his facial expressions, they're all ingrained in my mind.

When he stood up for Steve at our wedding, and when he met

our son, I saw a different side of Rick. The kinder, gentler, grandfatherly

Rick. No longer the boss, but still the Big Guy.

I called him for advice when I was eyeing whether to jump

from McClatchy, where I'd worked for over a decade, to go edit the newspaper

for the Catholic Diocese of Charlotte. I explained that it was less money but I

was working such long hours that I never saw my baby son. McClatchy seemed to be going

downhill fast, and the future didn't feel secure.

"What should I do?" I

asked.

He listened, then he reminded me of his test for any job:

"PT, does the money outweigh the crap?" Then he said, "The

Catholic Church has been around for 2,000 years. I don't think they're going

anywhere."

I took the job.

The most important lesson I learned from Rick happened in

Barnwell, one night in 1998 about 3 a.m.

I was tired of sleeping in the motel room in Winnsboro,

where he'd put me as publisher a few weeks earlier. I wanted to sleep back home

in Barnwell, in my own bed. So when I wrapped up work that night, I headed back

on the all-too-familiar drive down I-77 and Highway 3.

I fell asleep at the wheel just past the Barnwell County

line, waking up just in time to sideswipe the concrete wall of the bridge and

flip my car a couple times. It landed upside down in the middle of the road. As

I crawled out of the hole where the window used to be, I cut my elbow on some

broken glass, but other than that I was OK. When the ambulance dropped me at

the Barnwell ER, they asked me who they should call. The only family I had, I

said.

"Call Rick Bacon."

When he arrived and saw that I was all right, he gave me a

hug and cracked a few jokes to make me laugh. Then he took out a set of keys.

"What're those for?" I asked.

"Well, you'll need a car for a while, don't you?"

"You're going to give me the keys to your car, after I

was stupid enough to wreck my own car?"

"It's a piece of crap Buick. Have fun, Crash."

That was Rick. He never hesitated to help people in need, no

matter what. No questions, no demands, no exceptions.

In his last message to me, his voice was unnaturally soft.

But it was the same old Rick.

"Mrs. Guilfoyle, this is Rick Bacon. And I just wanted to

tell you that's a heck of a pope you've got now. He gives me faith that maybe

all religion isn't all totally crap. Just wanted you to know that. Have a good

day."

I hesitated calling him back, and got his voicemail when I

did call. I left a dumb, rambling message – not knowing what to say or what to

do, knowing it must have gotten pretty bad for him if he was talking about God

and religion without cracking a joke.

What I wanted to tell him is that he was a lot like Pope

Francis, and not just about their weight. I imagined him interrupting the

serious stuff I was trying to say, to joke about priests fondling young boys –

"Huh, huh," he'd grunt in his worst pervert voice – or about wearing

a cassock – "Do they wear any underwear under that dress?"

I wanted to tell Rick that soon after he was elected, Pope

Francis wrote an exhortation that spurred a lengthy interview with an Italian

Jesuit editor and it went global. The Pope, starting with that newspaper

interview, has recast the enduring Gospel message in a whole new light,

encouraging people think about letting God back into their lives, I'd say. Pope

Francis wants all of us to refocus on what's most important in life, because

it's not all about us, it's about how much God loves us, no matter what.

"The headline called the pope 'A Big Heart Open to God,'" I'd tell

him.

"You're just the same, Big Guy – except your headline

would be 'A Big Heart Open to People.'"

I wish I had had the chance to tell

him that, and to say, "I love you, Big Guy."